Puget Sound is home to a varied collection of place names that provide us with a tapestry of events, cultures and people that left their stamps on the region.

Of course, the original people named local places were the first people on this land. Native American tribes gave names to their lands, hills, prairies and waterways during the 20,000 years or so they have lived along Puget Sound before Europeans “discovered” the area. Many of those names remain today in and around Pierce County, with a growing roster of places with British or American names reverting back to their traditional names.

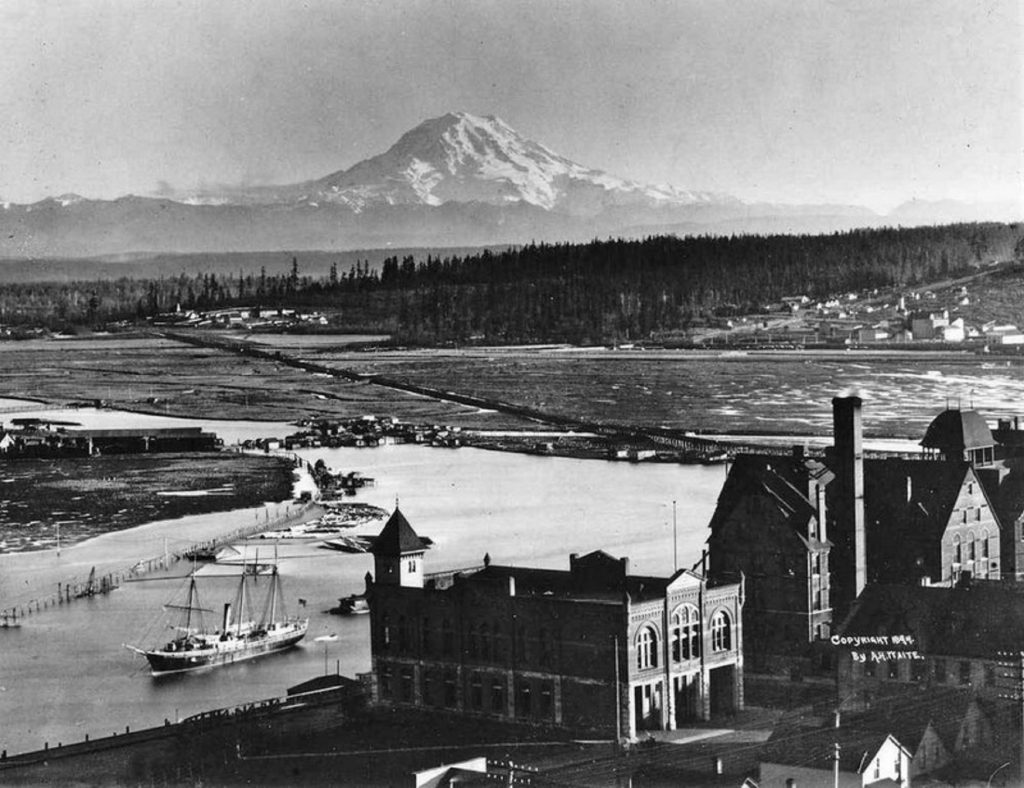

Mount Tahoma or Mount Rainier

The biggest renaming hill, so to speak, is possibly renaming Mount Rainier back to its traditional name of “Tacoma” or “Tahoma” in much the same way as Alaska’s Mount McKinley became Denali.

English explorer Capt. George Vancouver saw the majestic mountain and named it after his friend, Peter Rainier when Vancouver mapped the region in 1792. The “Rainier” and “Tahoma” names were used interchangeably for more than 100 years when the United States Board of Geographic Names officially endorsed the “Rainier” name.

But decisions made can always be unmade, so there is a smoldering effort to bring back the original name for Washington’s highest peak.

“I think it is going to be tough, but it needs to be done,” noted historian Michael Sullivan said.

The effort to return the Denali name took Alaskans 40 years, even with the strong evidence that locals around that mountain had used the Denali name all along.

Charles Wilkes Names Many Areas Around Pierce County

American explorers then took their turn at naming places, particularly Lt. Charles Wilkes. He visited and mapped the area in 1841. Names he gave to local geographic sites include Commencement Bay, named for where his mapping of Puget Sound started; McNeil island, after a captain of a local steamship; and Fox Island, after his ship’s surgeon. He came up with the name Gig Harbor for the simple reason that its bay was deep enough for a small vessel known as a gig.

What is interesting about Wilkes’ naming system is that he would get new maps from his cartographers and just write names that came to him, never seeing the island or waterway himself. He rarely left his cabin because he was so hated by his crew. They were so fed up with his heavy-handed and egotistical personality that they drew geographic features that didn’t exist to taint his legacy.

“There are islands on the Wilkes maps that don’t exist,” Sullivan said.

Gordon and Adolphus Islands, for example, appear on Wilkes’ 1848 map as just north of Orcas Island. Anyone who has traveled to the San Juans knows those islands don’t and never existed. They remained on maps for ten years.

Accurate or not, American settlers used the Wilkes’ names to settle the area in increasing numbers in subsequent years, adding their own names to places they settled or farmed. Tacoma’s Browns Point, for example, had been named Point Harris during the Wilkes expedition only to be renamed Point Brown in honor of an early settler, or Brown’s Point. The apostrophe dropped away to Browns Point, officially in 1901. A similar story came for the name of Point Defiance’s Owen Beach. It was named after a long-time superintendent of Metro Parks.

Lakewood and University Place are Named

Whatever a name is now, it might not last forever. Pretty much every area or geographic landmark has at least a Native American, British and settler name somewhere in its lineage. Names change all the time. What is now Lakewood and University Place, for example, weren’t cities until the mid-1990s, although those areas used those or similar names for generations until they were official.

University Place got its name back in 1895 when it was on the shortlist for what is now the University of Puget Sound. Lakewood was first simply called the Prairie by settlers of the 1850s. It was more commonly known as the Lakes District of Tacoma because of its recreational lakes as it developed after the turn of the last century. The name “Lakewood” became more popular in the 1920s.

How Washington Got its Name

For the record, the state was named after George Washington, the nation’s first president, as a compromise of sorts back when it started out as a breakaway territory from Oregon in 1853, after the title of the “Columbia Territory” was rejected. There was even then an effort in 1885 to change the name upon statehood to “Tacoma,” but that name didn’t stick, so “Washington” became the area’s designation in 1889, when it entered the union as the forty-second state.

If anyone wants to know why an area has its particular name, the late historian and Tacoma Public Library’s Northwest Room Director Gary Reese crafted “Origins of Pierce County Place Names” to answer all those questions.